On the NY Times article on ADHD

In April 2025, the New York times produced a long article titled "have we been thinking about ADHD all wrong?". A few pertinent observations about that

On Friday evening I was scattered. There was a literal “traffic jam in my head”. There were some four or five things to do at work, all requiring sufficient thinking, and I was unable to focus on any of them. My mind kept wandering from one to the other, trying to get ideas.

I decided that “from Monday onwards, I should restart Methylphenidate (Inspiral in India, Ritalin in the US). This scattering is too bad”, and then went for a walk.

Upon my return from my walk, I ended up hyper-focussing on one of those things, which was making a presentation that would guide my product’s demo video. I kept going with it late into the night, and could go into the weekend with a mild sense of accomplishment (when you are running your own company, your highs, at least in the initial period, aren’t that high).

And before I could take my Inspiral on Monday morning, I spent a long time on Saturday night finally reading a long form article ($) in The New York Times about ADHD, and whether we have been getting it all wrong. Among other things, the article reaffirmed why I’ve taken myself off the drug for nearly two years now.

With a set of quotes (from the article, all of them in italics) and my own thoughts, I’m documenting (primarily for myself, but also, as collateral benefit, for my readers) some pertinent observations from the article.

For starters, I have been extremely happy to get my ADHD diagnosis. It was one of those moments when “everything about my life so far got explained”. The big impact of this was that I stopped regretting the hundreds of prior decisions that i had made in life so far, and that I used to constantly fret about. The diagnosis, rather than the impact of the medication, gave me the biggest boost in terms of mental health.

I didn’t know this was the reason why extended release versions of ADHD drugs are so popular!

He advised Shire, which manufactured Adderall, a similar stimulant medication, on how to formulate an extended-release version of its product, so that children could take just one pill each morning instead of needing to visit the school nurse’s office in the middle of the day.

Interestingly, all times I took Methylphenidate, it was always the extended release version AND two times a day (once in the morning, once after lunch)This might sound scary, but to me, is unsurprising - speaking in electrical engineering terms, ADHD medication is “edge trigger” not “level trigger”. The impact on performance is from the impulse of having started taking the medication. After a few months, it becomes the new normal and you plateau.

It was still true that after 14 months of treatment, the children taking Ritalin behaved better than those in the other groups. But by 36 months, that advantage had faded completely, and children in every group, including the comparison group, displayed exactly the same level of symptoms.And some of the statistics quoted in the story are crazy.

Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 11.4 percent of American children had been diagnosed with A.D.H.D., a record high. That figure includes 15.5 percent of American adolescents, 21 percent of 14-year-old boys and 23 percent of 17-year-old boys.

A fifth of adolescent boys diagnosed with ADHD? Doesn’t sound right. The downside of so many kids getting diagnosed with ADHD is that it devalues the diagnosis of those who really need the help - you can run into “oh, ADHD is just a fad, keep quiet” kind of situations.One of the issues the article talks about is whether ADHD is a “binary” or “continuous” disorder. There is evidence on both sides. I strongly believe it is “continuous” and different people can have ADHD to different extents, and need different kinds of responses and management. And the one-size-fits-all questionnaire currently used for ADHD diagnosis may not be suitable in this aspect, and might be leading to overdiagnosis

Medical research hasn’t really done well in terms of getting biomarkers for ADHD. Sample this from the article:

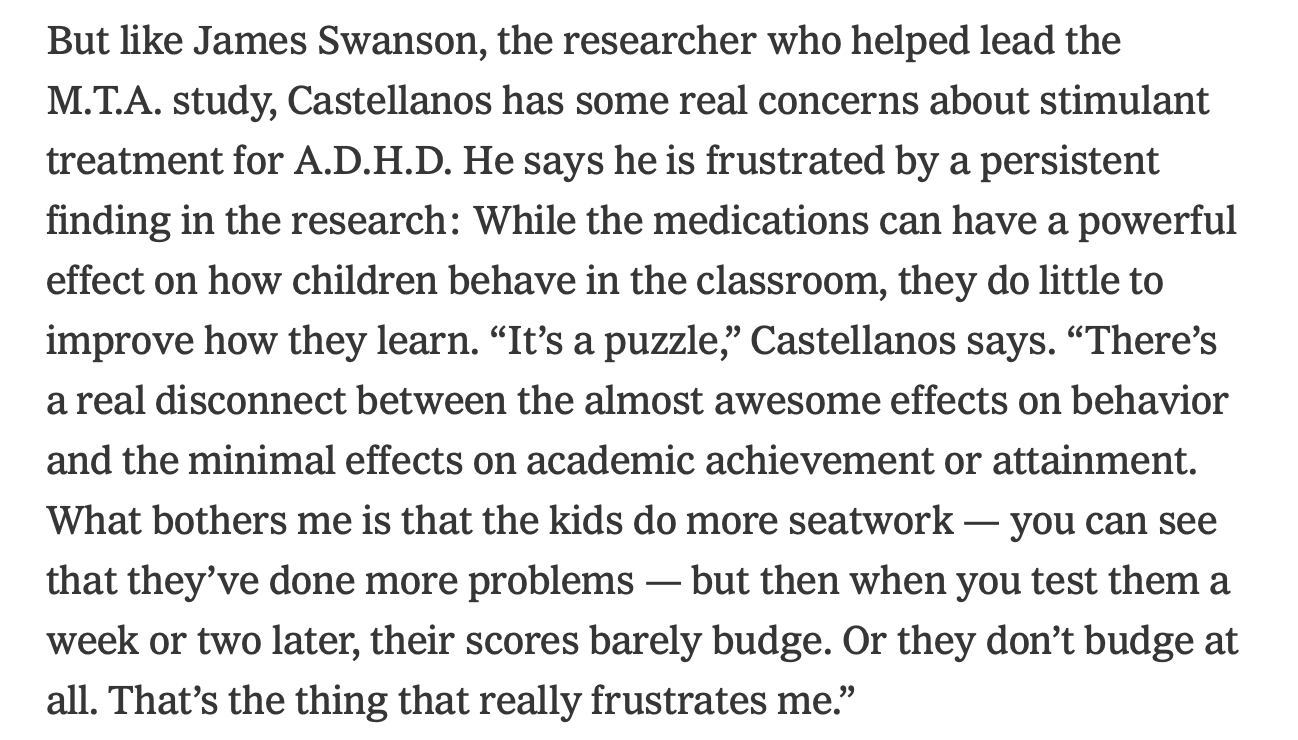

In the years since the consensus statement was published, however, the evidence for each of these A.D.H.D. biomarkers has faltered. Attempts to replicate the studies that showed differences in brain electrical activity came up empty. And though scientists have identified complex collections of genes that together may be signs of greater risk for A.D.H.D., they have failed to find a specific gene that predicts the disorder.This paragraph was, perhaps, for me, the real kicker in this article, and hence I’m screenshotting and pasting it in full:

Basically if you think of what happens in the classroom as a combination of “input metrics” (obedience, diligence, behaviour) and “output metrics” (performance) the research shows that ADHD medication make a marked improvement on input metrics but none at all on output metrics!

In other words, ADHD medication seems to give you the illusion that you are doing better and focussing better and are less distracted. Whether this actually helps you work better, nobody knows!Further evidence of the same concept a few paragraphs down:

The subjects who were given stimulants worked more quickly and intensely than the ones who took the placebo. They dutifully packed and repacked their virtual backpacks, pulling items in and out, trying various combinations. In the end, though, their scores on the knapsack test were no better than the placebo group. The reason? Their strategies for choosing items became significantly worse under the medication. Their choices didn’t make much sense — they just kept pulling random items in and out of the backpack. To an observer, they appeared to be focused, well behaved, on task. But in fact, they weren’t accomplishing anything of much value

Basically ADHD medication makes you more diligent. Whether you can put that to good use is another story!The point of the medications, though, seem to be that the increased diligence result in greater well being, and so you FEEL better when you are on the ADHD drugs. This is not strictly a placebo, but basically works at the meta level.

Without the pills, they said, they just didn’t feel interested in the assignments they were supposed to be doing. They didn’t feel motivated. It all seemed pointless.On stimulant medication, those emotions flipped. “You start to feel such a connection to what you’re working on,” one undergraduate told Vrecko. “It’s almost like you fall in love with it.” As another student put it: On Adderall, “you’re interested in what you’re doing, even if it’s boring.”

This is the scariest bit of the article for me. About how taking ADHD pills can stunt growth in children - up to an inch, which is rather significant!

In 2017, Swanson and the M.T.A. group published yet another follow-up, this time tracking the subjects until age 25. The ones who had consistently taken stimulant medication remained about an inch shorter than their peers. Their A.D.H.D. symptoms, meanwhile, were no better than those who had stopped taking the medication or who had never started.

Piecing together different parts of the story, it appears to me that ADHD medication makes you more diligent and polite, and so school teachers have an incentive to get it prescribed to their pupils so that they behave better in class. It doesn’t matter if the children do better - the fact that they are better behaved in class is enough incentive for teachers to get more of their pupils on the pill.

And the other important thing to note is that several studies, all quoted in the article, point out that there are no performance boosts by taking ADHD medication - it is basically about being calmer, and this feeling of calmness making you feel better. So methylphenidate is NOT a performance drug.

Ever since I came out with my neurodiversity and mental health issues (starting in 2012), several of my friends and acquaintances have approached me regarding their, and their children’s, neurodiversity. When it comes to the children, my advice has always been “to the extent possible, don’t let them know that they have ADHD until they are adults”.

This was largely based on my own experience (I was diagnosed fairly late, when I was nearly 30), with the explanation that if kids get to know that they are “different” they may not try as hard to figure things out in life. For example, the one downside of my ADHD diagnosis is that I now know that certain things are difficult for me, and so I simply don’t try! Also, knowing that certain things are difficult for me has made me more cynical and less open to new experiences.

Now I have yet another reason to not tell kids that they have ADHD - if they get on the pill it might stunt their growth, without actually improving their academic performance. And that is not a good thing.

Getting back to my bullet point observations:

I’ve had such experiences as well with ADHD medication - I’ve found that it’s massively stunted my creativity and lateral thinking.

Socially, though, there was a price. “Around my friends, I’m usually the most social, but when I’m on it, it feels like my spark is kind of gone,” John said. “I laugh a lot less. I can’t think of anything to say. Life is just less fun. It’s not like I’m sad; I’m just not as happy. It flattens things out.”

And “life is just less fun” seems like a big price to pay!Subject after subject spontaneously brought up the importance of finding their “niche,” or the right “fit,” in school or in the workplace. As adults, they had more freedom than they did as children to control the parameters of their lives — whether to go to college, what to study, what kind of career to pursue. Many of them had sensibly chosen contexts that were a better match for their personalities than what they experienced in school, and as a result, they reported that their A.D.H.D. symptoms had essentially disappeared

This is, frankly, a no brainer. One of the reasons I’ve spent large chunks of my adulthood working for myself (2011-20; 2024-) is that it allows me to spend more time on things that stimulate me, and that means I’ve been much more switched on a work and doing much better.

The setup also matters - I’ve outsourced a lot of things I find boring to my co-founder, employees and external consultants.

Last week I was deeply hyperfocussed on a work problem when it was time for a pre-scheduled meeting. It was a “high ADHD meeting” where I just couldn’t focus on the conversation and that was because, I think, I was focussed on the work I was doing prior to the meeting. I wasn’t able to take my mind off that (fairly stimulating, client-related) work, and so couldn’t fully pay attention to the conversation.

Completing the mental model on why a fifth of adolescent boys in the US are on ADHD medication - they are forced to spend long hours doing things they don’t find stimulating (sitting through lectures in a classroom), and so they are bored and possibly disruptive. Their teachers know that putting them on ADHD medication is going to make them behave better, and so recommend it. And so more and more kids get such diagnoses.

Once they are out of the stifling confines of the classroom, and can choose what they can do, they are able to concentrate much better. ADHD goes out of the window, as does their pills!

The article does seem cynical about ADHD, and maybe the writer has an agenda. However, it confirms enough of my biases that I didn’t take the Methylphenidate today, and I don’t plan to take it tomorrow, or any other day. I stopped growing taller 25 years ago, so this is not related to that!

Normally, on this blog, I like to edit what I’ve written. But this piece has gone on for so long that I now don’t have the attention span to edit or review what I’ve said here! I’ll just hit send.

Karthik: Wow. Thanks for sharing! I read it start to finish

I think one of the most important points left out in this article are the benefits kids get socially on the medication. Impulsivity, emotional reactivity, picking up on social cues are big challenges with adhd. On the medication children don’t just behave better for their teachers they behave better with their classmates. This is a huge component for self-esteem and building friendships. Especially when kids are young and still developing their impulse control.